The NHS is facing a mounting crisis, with experts revealing that extreme health inequality across Britain is costing the service up to £50 billion a year.

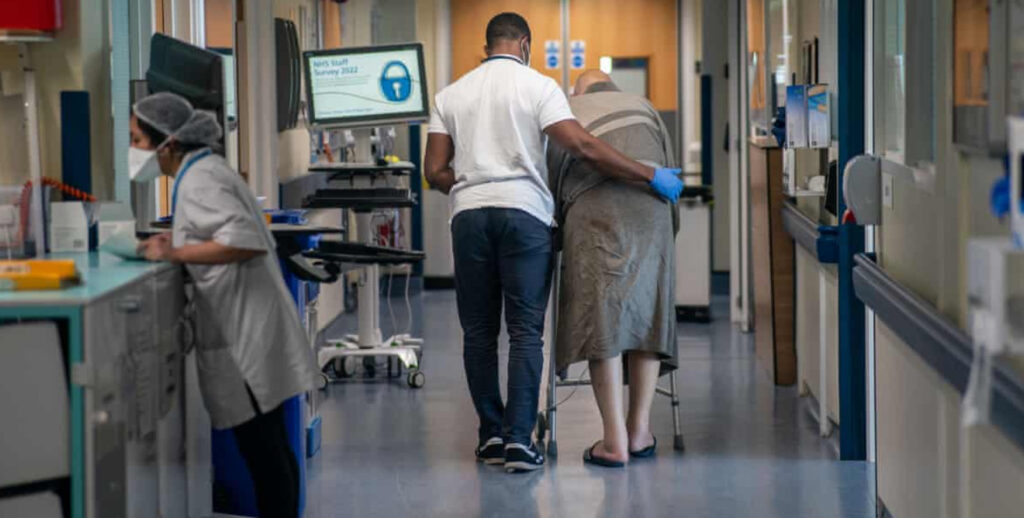

This growing burden is largely driven by rising deprivation and child poverty, putting immense pressure on hospitals and GP services.

Despite the government’s recent pledge to increase NHS funding, the deep-rooted impact of poverty continues to fuel demand across the health system.

Hospitals report seeing shocking levels of untreated illness in some of the country’s poorest areas, alongside a resurgence of conditions once considered consigned to history, such as scabies, rickets, and scarlet fever.

An investigation into the link between poverty and the NHS crisis highlights that worsening deprivation is resulting in increasing hospital admissions and delayed care. In some cases, vulnerable individuals are even self-harming to secure temporary admission. The NHS is now said to be spending sums equivalent to the UK’s annual defence budget dealing with the fallout.

The chancellor recently announced a £29 billion real-terms rise in NHS spending by 2029, but concerns remain that cuts to social care, housing, and poverty reduction programmes are undermining overall health outcomes.

The health secretary is due to launch a 10-year plan aimed at shifting the NHS from treating illness to preventing it. However, NHS leaders are warning that the government’s goals may be unachievable unless wider social inequalities are addressed.

Nearly half of all regional care boards are facing deep cuts, with up to 12,500 job losses expected by year-end. Health professionals argue that prevention must be accompanied by investment in communities most affected by hardship, particularly children and families facing the brunt of the cost of living crisis.

A previous study by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation estimated that poverty-related illness cost the NHS £29 billion annually in 2016. Experts now believe that figure could have risen to £50 billion or more, given the increased number of people facing hunger, destitution, and inadequate housing.

Research shows that around a quarter of NHS spending in primary and acute care can be attributed to increased use by those living in poverty. Emergency hospital admissions are nearly 70% higher among the poorest compared to the most affluent groups, and A\&E visits are almost double.

Air pollution is also having a serious impact, disproportionately affecting deprived areas and contributing to 30,000 deaths annually, along with a £500 million weekly cost to the NHS and the wider economy.

Without urgent action to reduce poverty, health inequalities are expected to widen over the next two decades. Those in the poorest areas are being diagnosed with serious illnesses up to 10 years earlier than people living in wealthier regions, according to data from the Office for National Statistics.

Public health leaders are calling for systemic change. They argue that without decisive policy to improve living standards, the NHS will remain overwhelmed and unable to deliver equitable healthcare.

The government maintains that it is committed to supporting the most vulnerable. Ministers have announced measures such as a £1 billion reform package for crisis support, free school breakfast clubs, increases to the national minimum wage, and fairer repayment terms for universal credit deductions.

In addition, more than 3.6 million extra NHS appointments have been delivered since July in an effort to reduce waiting times.