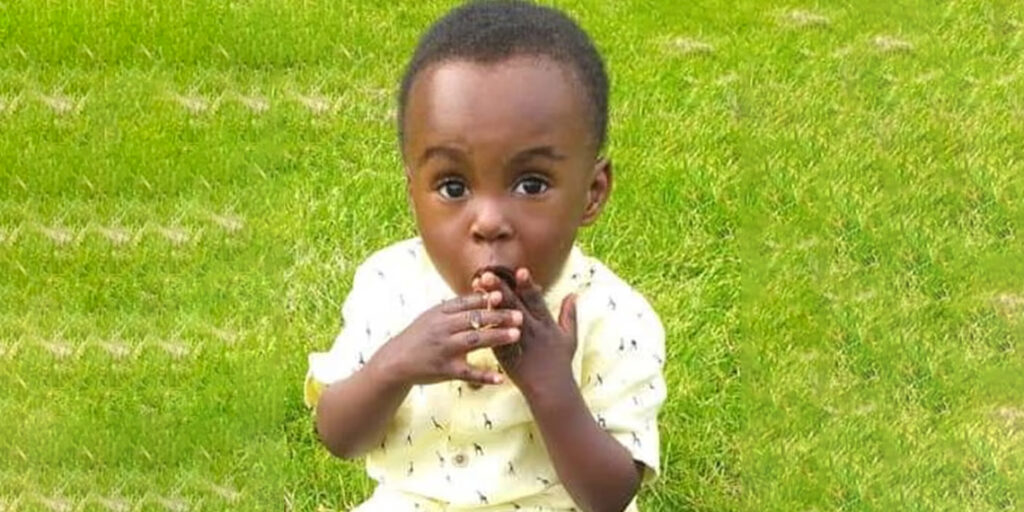

England has officially implemented the first phase of Awaab’s Law, a landmark housing reform that forces social landlords to fix serious health and safety issues within strict deadlines. The legislation, which came into effect on Monday, is named after two-year-old Awaab Ishak, who died in 2020 from a respiratory condition caused by mould in his family’s rented home in Rochdale, Greater Manchester.

The law introduces legally binding timeframes for landlords to investigate and repair unsafe housing conditions, marking one of the most significant overhauls of tenant protection in years.

What Landlords Must Now Do Under the New Law

Under Awaab’s Law, social landlords must fix emergency health and safety hazards within 24 hours of being reported. Significant mould and damp complaints must be investigated within 10 working days, with repairs completed within five days after inspection. Landlords must then provide tenants with a written summary of the findings within three days.

The new measures also require landlords to consider tenants’ personal circumstances, including the presence of young children, disabilities, or health conditions that increase vulnerability. If a home cannot be made safe within the timeframe, tenants must be offered alternative accommodation.

A Legacy Born from Tragedy

The reform was introduced in memory of Awaab Ishak, whose death exposed long-standing failings in social housing maintenance and accountability. Following a high-profile campaign by his family and the Manchester Evening News, the UK government pledged to ensure such a tragedy could never happen again.

Housing Secretary Steve Reed said:

“Everyone deserves a safe and decent home to live in, and Awaab Ishak is a powerful reminder of how this can sadly be a matter of life or death. Our changes will force landlords to act urgently when lives are at risk.”

Nationwide Concern Over Mould and Damp

The new law comes amid growing alarm about unsafe living conditions across the UK. A recent Censuswide survey for the Health Equals campaign found that 23% of people reporting problems like damp, mould or condensation were social renters, while 21% lived in private rented homes.

Campaigners warn that damp and mould are directly linked to respiratory illnesses and premature deaths. They are now urging the government to extend Awaab’s Law to the private rented sector without delay.

What Comes Next: More Protections on the Way

Phase 1 of Awaab’s Law focuses on mould, damp, and emergency hazards. Phase 2, scheduled for next year, will cover additional dangers such as excess cold and heat, fire and electrical risks, and hygiene hazards. By 2027, Phase 3 will extend protections to all other threats under the Housing Health and Safety Rating System (HHSRS) — except overcrowding.

The government has already pledged to apply Awaab’s Law to private renters through the Renters’ Rights Bill, which completed its passage through Parliament on 22 October 2025.

Implementation Challenges for Housing Providers

While the reforms are widely welcomed, housing professionals warn that real-world implementation will be challenging. The Chartered Institute of Housing said social landlords have been preparing new systems to meet the legal deadlines but urged the government to provide long-term funding and clear guidance.

Chief Executive Gavin Smart noted:

“This is a significant step in ensuring all social housing tenants live in safe and decent homes. Awaab’s Law provides a vital new framework for addressing serious health and safety concerns, beginning with damp and mould.”

However, industry experts caution that local authorities and landlords will need additional staff, training, and resources to meet the rapid response standards now required by law.

A Turning Point for Tenant Safety

Awaab’s Law represents a new era of accountability in England’s social housing sector. For the nation’s four million social rented households, it offers a clear message: neglecting unsafe homes will no longer go unpunished. Landlords who fail to comply face court action, enforcement orders, compensation claims, and legal costs.

The law stands as both a tribute to a lost child and a firm warning to housing providers — that the cost of inaction can no longer be counted merely in money, but in lives.